Beginning to settle in

The past week has seen me working on a variety of tasks at work – including (but definitely not limited to) making new information displays for the visitor centre, writing Facebook posts for the Trust, rearranging some of the interpretation at the centre, starting research into a report that I will be writing and of course, the usual running of the visitor centre for the long weekend (Fri-Mon).

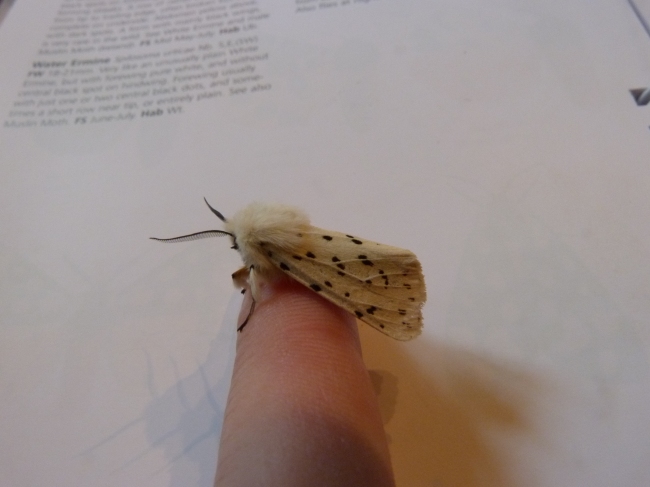

I say “the usual”, but each day is different! I see different species, particularly if I’ve been moth trapping or decide to go out with a sweep net (tomorrow’s plan), listen to a variety of programs as I work if the centre is very quiet (mostly Radio 4 – Just A Minute, Ramblings, Inside Science and Costing The Earth), and every time someone walks into the centre, I know that something new will happen. I have had such a variety of conversations this week – the politics of conservation, the process of CRB checks and the Scouting movement, the bizarre forms of ladybird larvae, and of course, how cool moths are! Inevitably, I meet at least one new dog every day which I absolutely love.

So a round-up of some of this week’s wildlife. Not many butterflies as the summer draws to a close, but I did see a new favourite of mine – the Small Copper Butterfly. And I took a photo of it that is now one of my favourite butterfly photos that I’ve ever taken. It was resting on the wall of the Visitors Centre above my head, and I had to lean into the wall and look up to get the photo. I feel like it’s thinking “What are you doing?!” There were also moths about of course, including some new ones for me such as the Autumnal Rustic, Hedge Rustic and Rosy Rustic (I sense a theme …), and the ever-fabulous Canary-shouldered Thorn.

- Red Admiral Butterfly

I also found a dead bee, which made me sad. But I took the opportunity to study it closely, and saw that what I believe is it’s tongue sticking out the mouth. There are three parts to the tongue it seems. Very interesting, and now I want to look into bee anatomy.

Towards the end of the week, I went to a local theatre production by Mid-Powys Youth Theatre at the Willow Globe (open air theatre- my favourite!). They were performing Humans On Trial – An Ecological Fable, and they were fantastic! The premise is that humans are trial for their actions against animals. With witnesses, a judge, a prosecution lawyer and a defence lawyer, the crimes of the accused are laid forth and debated. It’s a great play and very thought-provoking. If you get the opportunity to see it, do so!

- The Turtle looks back on his years of experience to discuss humans and their interactions with nature.

- Head Rodent of the Oxford Bodhelian Library answers questions from the defence lawyer

- The Owl Judge stands ready to deliver his verdict. Humans – guilty or innocent?

Next week should bring even more variety as I continue moth trapping, go out with the sweep net, potentially assist on a bat survey, sort through some of the interpretation at the centre (including skulls!) and attempt some wildflower identification.

You can follow the wildlife, news and events of Gilfach by following #GilfachReserve on Twitter!